Here in Elementary Social Sciences, we have been trying our hands at making games!![]()

And students can make games too! Here is a process you can follow, for this project and for others.

Below are a series of guides and planners to summarize some of our experiences and to help you and your students get started designing and making games for social sciences.

A few Pre-Game Creation Practical Considerations

First, let’s get some basic, practical considerations out of the way:

- The game’s pieces, tools, and resourcesResources are anything taken from the earth or nature that people need, use, and are "valued".... should be free and easily copied by teachers and students.

- The technologies used to make the game should be free and accessible, and not likely to be deprecated, to eventually require costs, or to be discontinued in the future. (For example, we use Google drive technologies and do not recommend using online gaming tool sites like Kahoot.)

- The gaming idea and tools could be shared back for provincial use, or as a model for local use in other communities. Before you start you might want to check our Padlet that lists some completed and incomplete ideas for games that are in the works. Looking for inspiration? We have a working Google document for that!

- NEW: Guides to help students think of ways to design their own games by @recitus .

Visit CONCEPTION D’UN JEU SÉRIEUX AVEC LE LAB CRÉATIF [English student booklet is here!]

Now let’s think about Design-Thinking for Game Creation in Social Sciences

Click above for a printable PDF version for group brainstorming.

Or click here to open ledger-sized version Google Slides![]()

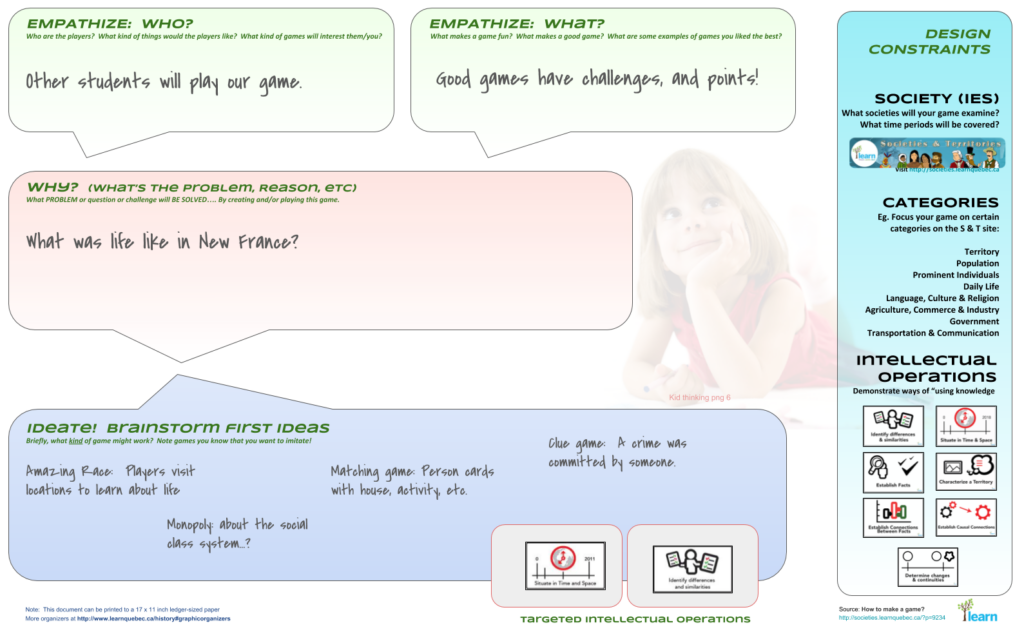

The original impetus for the first games created on this site came out of various Design Thinking workshops offered at LEARN itself. Then, recently an article on our blog (The Design Process: The backbone of school Makerspaces) helped to explain the what, why and how of design thinking in the classroom. Based on that article, the student tool by Diana Rendina displayed there, and various other references (For example, Design Thinking 101, and 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process), and keeping in mind the program competencies and the intellectual operations being evaluated, a game-creation strategy and planning tool![]() was developed. Below are the basic steps in that document with additional explanations and suggestions. (Oh, and here is a nice new poster from our RECIT friends you can also use on your wall!)

was developed. Below are the basic steps in that document with additional explanations and suggestions. (Oh, and here is a nice new poster from our RECIT friends you can also use on your wall!)

![]()

Empathize

A familiar concept, you should consider your audience! After all, you are making a game for someone to play. Think about who is involved: “Who are the players? What kind of things would the players like? What kind of games will interest them?” And, try to make a game to which players can relate.

Likewise, you already know what kinds of games are fun to play, how games work, what makes a game fun. Use your own experience to answer questions like, “What makes a game fun? What makes a good game? What are some examples of games you liked the best?”

Why are you making it?

Why are you making it?

What’s the problem this game will solve? What’s the reason you are building it? What question or challenge will be solved by creating and/or playing this game?

Here we are justifying our game building project in several ways: First, we are saying why it will be fun, motivating, different. Second, we are often creating a game to build bridges between its creators and the players: what each group will “take away” from the game needs to be considered. (For example, your school or community members could come and play and learn from your game!). And third, in this case, we are definitely building it to fulfill a pedagogical goal: to learn about societies and historical events, to practice historical thinking and methods (i.e. competencies!), and to check and be evaluated on how we are able to “use knowledge” (i.e. the Intellectual Operations!)

Ideate: Brainstorm initial game ideas that might work

Here is where you throw out a few ideas of games you liked or games that came to mind when you targeted a society or time period, categories from the S and T site, or certain specific intellectual operations. “Briefly, what kind of game might work? Note games you know that you want to imitate!”

There are no rules for how you come up with gaming ideas for the social sciences. The games we have produced were usually directly inspired by earlier games, and in fact, since the materials (the cards, etc.) from those games were easily copiable, the next game idea often resembled and only slightly varied from the one before it: a different society, a different I.O., and then a different idea naturally came out of that. At other times another game, or just a fun activity, inspired a game idea, something that could be done with historical events or key figures or even locations, instead of the what the original game suggested. Again, browse a few some of our past efforts at “ideating” here on this Padlet.

![]()

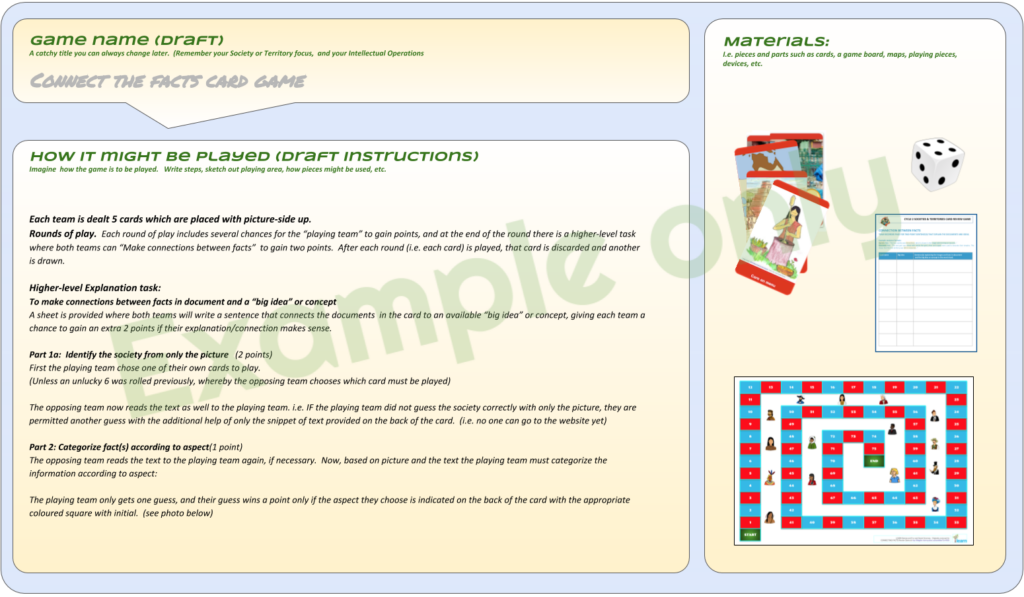

Prototype it

Here is where you start to build the first version(s) of your game. Your game will need 1) a catchy title. You already know by now where your game is going, so get it part way there by giving it a draft name. (Remember your Society or TerritoryA territory is an area of land, or sometimes of sea, that we can say "belongs"... focus, and your Intellectual Operations. Include references to those in your title or sub-title). Your game will be played with 2) materials: pieces and parts such as cards, a game board, maps, playing pieces, and it may use electronic devices as ours did for research or verification purposes. And of course, 3) How might your game be played. In point form, write up some draft instructions, for you to imagine the flow of the game, who does what, how points are won. You could even sketch out a playing area or include any existing photos or screenshots demoing your game.

What does prototyping it mean? Well, now you can start to build those materials, set up your game, try it yourself, show it to your peers. You may want to use some of the Testing & Redesigning templates below, during this phase too, to note down what needs to be adjusted as you are working it out.)

Remember, the vast resourcesResources are anything taken from the earth or nature that people need, use, and are "valued".... on the Societies and Territories site make it easy to grab texts and images you can use to create learning and evaluation games. If you focus on a specific society, or a few societies in a time period, or even just certain categories within a society, it will make your game building easier. Remember your goal, the Why of your making this game in the first place… though you can always simplify or change ideas during the building process. Once a playable version is ready, you can really try it out with a target audience, to see if it makes sense, promotes learning, and is really fun. But first, make sure your instructions are clear:

Remember, the vast resourcesResources are anything taken from the earth or nature that people need, use, and are "valued".... on the Societies and Territories site make it easy to grab texts and images you can use to create learning and evaluation games. If you focus on a specific society, or a few societies in a time period, or even just certain categories within a society, it will make your game building easier. Remember your goal, the Why of your making this game in the first place… though you can always simplify or change ideas during the building process. Once a playable version is ready, you can really try it out with a target audience, to see if it makes sense, promotes learning, and is really fun. But first, make sure your instructions are clear:

![]()

Writing up your (first) ready-to-go version: Instructions and game materials

What’s in the box? How is it played? What are the rules? And since this game is really about learning, what do you hope your audience learns from this game? It’s time to write up your game instructions.

We suggest using an easily editable tool like a Google Document because you will make changes! It also allows you to easily drag or paste in images of your materials, and to link to other documents you will need. Google Draw can be used to make cards, game boards, and other materials. And remember, use the spell checker! Print out all your instructions and materials too, to check for quality, colours, etc.

![]()

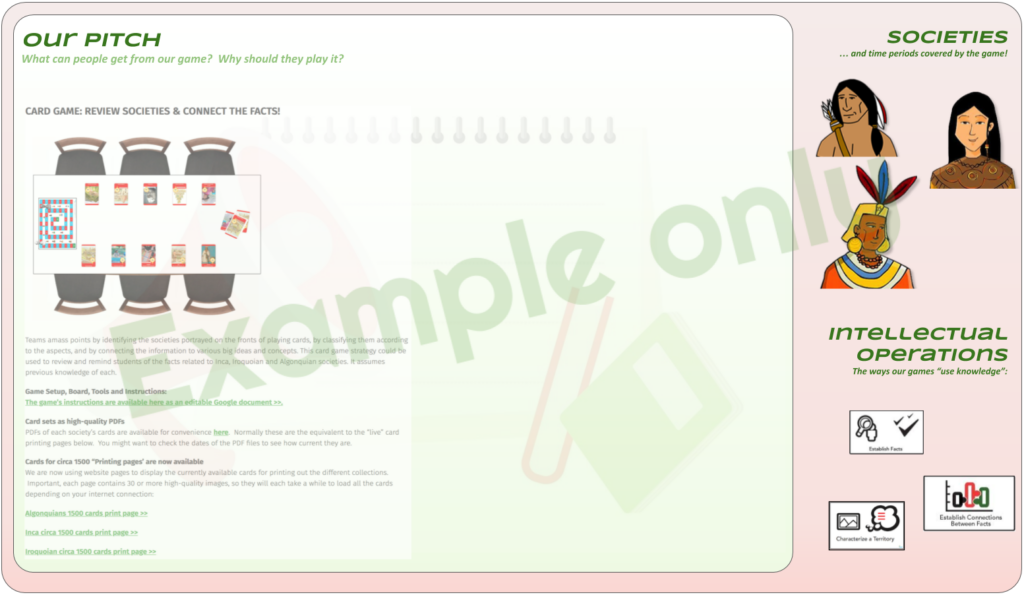

Test Runs: Evaluate your game

Take notes while people are playing your game. Observe which elements worked well, which elements didn’t, whether it was fun and whether the expected learning took place. Ask the players to tell you what they thought was fun and how they would like it improved. Is there a variation of your game that might work better (or that could be an inspiration for a second game you could create with the same materials!)

Redesign it: What needs to be changed?

Yes, you have already prototyped a few versions by now, but it’s only after a real-world test (or two or three) that you will be able to know if your new game is playable or not. Now it’s time to improve it, make it better, refine your original design based on feedback and your own experience of watching people play it. Other elements of your game may also require re-designing, including the materials you created, and even the “way” you created those materials. Remember, the game needs to be easily and quickly copyable, editable by teacher or students, using free technologies others can access… Your redesign might also re-consider all these aspects, and more that come into question the more the game is accessed and used!

![]()

Announce your game, spread the word, share it out a well-tested versio, celebrate!

Your game is now ready to be shared with other students, teachers, and even community members. Since your game is based on History (or Geography!) and the Quebec provincial programs, consider sharing it out on the Societies and Territories site itself, in our growing game collection area. Even if (and especially if!) your game is about local history or experiences, consider posting it, so that other communities could use as a mode. Announce it through the greater LEARN network and via our partners. Contact Paul R. at LEARN by email or by tweeting it to me directly at @paulrombo